Some Thoughts on the Maximian Ontology

Following from Fr. Hans Boersma's "Architecture and Metaphysics"

So, I just finished reading the article “Architecture and Metaphysics: Sacramental Ontology in Maximus the Confessor” by

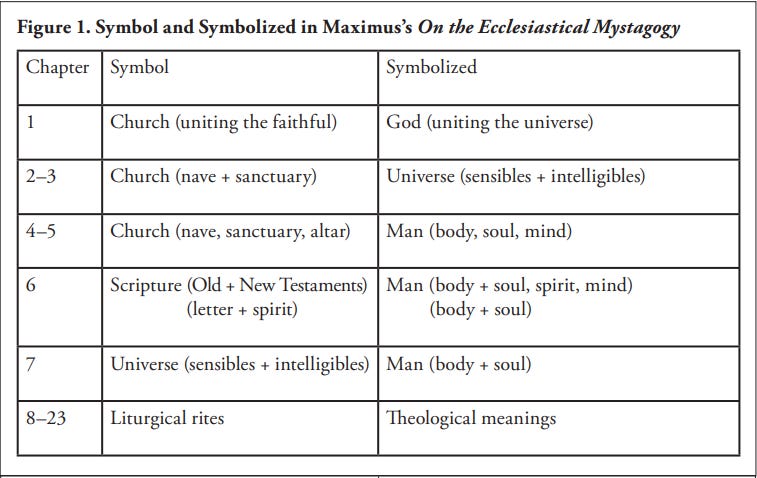

, which is a simple but provocative discussion of the theology of St. Maximus the Confessor. It’s nice, I think it’s a good propaedeutic for what, from experience, can be the very sophisticated world of Maximian theology (although a rewarding world). Go read it if you can!Since I like to make use of whatever I study in what I write and I believe I’ve communicated that in some way in the past), I thought some thoughts I had in reading through that article could prove conducive to a short but thought-provoking post. This mainly concerns the significance of some equivalencies that Fr. Boersma makes note of, which are highlighted in Figure 1 of his article, as shown below.

As Fr. Boersma explains, Maximus’ book On the Ecclesiastical Mystagogy is entirely devoted to explaining this: “He wants his catechumens to know how nave and sanctuary, intelligible and sensible realms, the various human faculties, and letter and spirit relate to each other” (p. 19). He wants this so as to make clear to the catechumens the nature of the Church they are entering into, not just as a building or community, but even more powerfully as a cosmic reality itself. So his book serves as “a catechetical manual of sorts, dealing with a variety of topics, showing the interconnectedness of things, and drawing upon the doctrine of God, anthropology, cosmology, hermeneutics, and liturgics, as well as architecture” (p. 22).

Now, given this, I noticed something as I read through the article. Since Fr. Boersma clearly states that in Maximus’ view these different elements are related as I saw him make use of those terms I began thinking: “Hmm…so if this means that, what sort of understanding would be begotten if we exchanged the equivalent terms?” Let me just show you exactly what I mean. Here below is a sentence from the article, which itself is a direct quote from Maximus:

The nave is identical to the sanctuary according to potency (dynamin) because the nave is consecrated by the anaphora at the consummation of the mystagogy and, conversely, the sanctuary is identical to the nave according to act (energein) because the sanctuary is the place where the never-ending mystagogy begins. The church remains the same through both.

Now, go back to Figure 1. We’ve already been treated to the understanding that nave is related to the sensible, and to the body (based on chs. 2-3 and 4-5).However, going further we also can see that if this is true, then since nave correlates to body (chs. 4-5), and body correlates to the sensibles (ch. 7), then the sensibles are equivalent to the nave! Following the various connections like those grade school matching exercises, we eventually log the following connections, as I summarized in an annotation:

Logoi = intelligible = sanctuary = soul = New Testament = spirit (vs. letter)

Created order = sensible = nave = body = Old Testament = letter (vs. spirit)

Interesting stuff. Let’s apply this now. Consider that first quote from Maximus, if we swapped nave and sanctuary out for body and soul it’d read this way:

The body is identical to the soul according to potency (dynamin) because the body is consecrated by the anaphora at the consummation of the mystagogy and, conversely, the soul is identical to the body according to act (energein) because the soul is the place where the never-ending mystagogy begins.

I’ll also do this for logoi and the created order before trying another exchange:

The created order is identical to the logoi according to potency (dynamin) because the created order is consecrated by the anaphora at the consummation of the mystagogy and, conversely, the logoi are identical to the created order according to act (energein) because the logoi are the place where the never-ending mystagogy begins.

Now, given the growing significance of Maximus’ theology in modern theologizing I think this is very interesting to think on. If these things are related, as Fr. Boersma states, if body and nave correspond, and symbolize the soul/sanctuary, and even further the created order and logoi, what does that truly mean? This is definitely something worth discussing because Fr. Boersma doesn’t get into himself, and it’s a realization I solely came up with in reading the article. Here’s another section of the article, and then its exchanged versions:

The sensible realm is in the intelligible realm in the principles (logois), and the intelligible realm is in the sensible realm in the representations (typois).

Here’s body and soul:

“The body is in the soul in the principles (logois), and the soul is in the body in the representations (typois).”

One more, this time using Old Testament and New Testament:

The Old Testament is in the New Testament in the principles (logois), and the New Testament is in the Old Testament in the representations (typois).

Two things I think are worth pointing about this particular instance: first, is this interiority being additionally affected by being “in the principles/representations” an indication that the logoi aren’t directly related to the sensibles but mediated by the intelligibles? When Fr. Boersma goes on to say that the “eternal logoi impress themselves upon the observable created order, while the latter is present in the former” and the “intelligible logoi impress themselves upon the observable created order and so are present within the sensible types” (p. 20) he seems to directly correlate logoi/intelligible and creation/sensible, collapsing the distance alluded to by the direct quotation from Maximus. That invites bearing out. Second, doesn’t that second exchange, concerning the two testaments, sound an awfully lot like Augustine? “The New Testament revealed what was veiled in the Old Testament.”1 It would seem that this exchange could have important implications for a theology of revelation.2

Bringing this together here are some thoughts I have, which definitely would be fruitful to bear out. There are definitely powerful conclusions to draw from the equivalent relations we've identified. Originally, there is the potency in the nave to become as the sanctuary through liturgical action. Taking that further, can it be said that the body can be “elevated to the level of the soul,”3 suggesting a unity where the physical is spiritualized? That would certainly seem to accord with what Boersma says about Maximus’ ontology: “[He] was a staunch advocate of the unity of nature and the supernatural” (p. 16). Moreover, when we come to the exchange “The body is in the soul in the principles (logois), and the soul is in the body in the representations (typois)” what we find seems to suggest that the soul informs the body through its inherent principles, while the body manifests the soul through visible forms. Is that right? What does that look like borne out? (That’s becoming the word of the day it seems.) Likewise, with Scripture can we read this as saying the Old Testament has the potential to be fulfilled in the New Testament, while the New Testament actively realizes this potency, as seen in typology and prophecy? Or, following from that second exchange, do we there have an understanding that the Old Testament contains the New Testament in its deeper meanings, whereas the New is prefigured in the Old through types? Here we might see something of a metaphysics behind intertestamental dynamics, and insofar as this originates in Maximus’ discussion of liturgy there’d be a conclusion to draw that in the Church’s worship the Scriptures are fully realized.4

Now, here’s where I’m wondering about a potential snag: if the body or created order is elevated to soul or logoi, could that sound like the body becomes spirit, losing its physicality? At risk of sounding Gnostic, we’d have to think that through. Perhaps one of our exchanges has the answer, “The whole soul is impressed mystically in symbolic forms upon the whole body.” This relation is not so much of the body being overridden, but of the body being “exalted.” Maximus’ Chalcedonian foundations would/should certainly serve as a temper, because per the Definition the divine in Christ doesn’t subsume the human, nor vice versa. Moreover, when Fr. Boersma explains that “in Maximus’s church” we see the “act (energeia) of the priest’s consecration is applied to the nave; and when the nave’s potency (dynamis) receives this act, the nave reverts back to the sanctuary” (p. 20) this clearly implies an ontological continuity in the consecrated nave, meaning it doesn’t become something different. So the analogically “consecrated” body should still retain its physicality as the nave retains its naveness?

To tie all this into another angle, ever since it was introduced to me via Gavin Ortlund I’ve always thought of George Hunsinger’s proposed ecumenical sacramentology, centered on “transelementation,” to be very intriguing and promising.5 Hunsinger’s model of transelementation is described by him as being akin to how an iron rod, if placed in fire, takes on the heat of fire, and thus can be said to truly and indelibly take on the being of fire, but without becoming identical to the fire. This might provide a basis for understanding Maximus’ ontology, for in the same way Hunsinger’s sacramentology preserves the “generic breadness” of bread6 the movement of the body-nave into the sanctuary-soul means that the body is “spiritualized” analogous to transelementation, being shaped by the sanctuary-soul but without losing its bodiness. It’s very interesting, but if we’re going to draw a connection between Hunsinger and Maximus here there’s a second snag that might arise: Maximus’ connections detailed by Fr. Boersma are said to be based on a Chalcedonian model (pp. 19-20), which is fine only until we realize that if Hunsinger’s model is to be correlated to Maximus’ then the latter’s Chalcedonian foundations can’t be kept to.7 The Chalcedonian Definition states, as Boersma states, that Christ’s two natures (divine and human) are undivided and without confusion (p. 19); that is, Christ is fully divine and fully human, both natures exist fully and completely within Him. But, Hunsinger states that whereas the substance of iron is fully present, it’s an aspect of the heat of the fire that’s communicated to the rod. This isn’t a matter of “ontic totality.” But per Chalcedon an “aspect” of Christ’s divinity wasn’t just “communicated” to His humanity, His humanity wasn’t just “heated up” by His divinity, it fully and completely coexisted without confusion or division. Two things I can say concerning that: first, perhaps I’m misunderstanding Hunsinger, after all, he explicitly demonstrates awareness of Chalcedonian theology in his work;8 second, since this sounds a lot more like Lutheran sacramentology, as described by

here, perhaps all we need to do is become Lutherans? Doesn’t sound that difficult.I think everything here is quite pregnant, insofar as my original connections/equations are appropriate, and that’s why my intent here is primarily to instigate further discussion. I know my limits, and I’ve only just begun studying Maximus with intent, Boersma’s article being part of that. Maximus definitely was a rich Father, and

is a scholar I respect, and insofar as both men deserve their theology being taken deeper, what, if anything, I’ve picked up on in reading this article I’d hope is conducive to that.Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, 211 (V.18); cf. Quaest. in Hept. 2.73 (PL 34).

Consider another statement just before in the text: “The whole intelligible realm is impressed mystically in symbolic forms upon the whole sensible realm,” which can be exchanged as, “The whole New Testament is impressed mystically in symbolic forms upon the whole Old Testament.”

However we wish to phrase this phenomenon. (That can be borne out too!)

Having once read long before Boersma articles by the Catholic theologian Scott Hahn on liturgy and the history of the scriptures this takes on renewed significance. See S. Hahn, “Worship in the Word: Toward a Liturgical Hermeneutic,” Letter & Spirit 1 (2005): 101-136; and idem, “From Old to New: ‘Covenant’ or ‘Testament’ in Hebrews 9,” Letter & Spirit 8 (2013): 13-34; cf. idem, Consuming the Word. See also A. Yong, Spirit-Word-Community.

See “Karl Barth on the Lord’s Supper: An Ecumenical Appraisal,” essay in Conversational Theology, G. Hunsinger, 21-44.

I.e., the consecrated Host is still chemically/ontologically the same as bread you’d buy in the store, but is more than that still.

And given that, thusly, either Maximus’ or Hunsinger’s model would have to be disciplined as a result, one would want to naturally preserve Maximus due to his preeminence. Sorry, George.

Hunsinger, Conversational Theology, 23, 31, 32, 41; cf. 141-43.