What Aristotle Teaches Us About Youth and Life

Observations from the pen of the wisest of the Greeks and the foolishness of the moderns.

A (hopefully) quick discussion today. One thing I’ve for some time now been focused on is the issue of how many modern (Western) young adults are living and conceiving their lives. I believe they’ve drawn the short end of the straw in the emergence of “modernity” and the institutional, cultural, technological, and rhetorical devices that define the resultant civilization. Especially for young1 men, in a time defined by its practices of grievance politics, struggle sessions, identity politics, and other techniques often labeled as “Wokery,”2 there is no better target for the expression of these techniques and concepts than themselves.3 For our long history of intrinsic strength (among other defining features) men have been “on the top,” and being on the top we’ve unduly imposed ourselves on those “on the bottom,” i.e., women; accordingly, given the aforementioned devices and techniques, a masochistic “collective male guilt” has been fostered by certain elements that has served only to crush the spirits of males.4 I needn’t and am not seeking to overlook the role young women play in this, as I’m very much concerned about their well-being, too. We can’t overlook how women have been similarly victimized and undermined by the specter of modernity, being browbeaten with false idols of femininity and the fruits of a “liberation” akin to the experience of being liberated from one’s grip on the cliffside they’re dangling off of.5 As the statistics show us,6 the young adults are suffering enormously, regardless of socioeconomic, academic, racial, or sexual factors, and accordingly I have enormous concern about them.

Why? Well, other than being among and dealing with them quite frequently, and being one myself, there are greater reasons why. Twofold: firstly, as a rather notorious German man once put it, “He alone who owns the youth gains the future.” This is true, it’s not debatable, it’s just that often the wrong people realize the truthfulness of the statement. However, what happens when the youth are out of control, so that no one can gain control of them? The answer necessarily is that the future is cast in darkness. While many things have cast the future of civilization in darkness (things that are broadly called, such as by myself, “the crisis of modernity”) the particular thing that is the systemic despair of our youth is as good an indicator as any.

Secondly, youth is a great thing. Youth, especially if defined7 as 15-24 (maybe a bit later), is the time of vigor, discovery, ardor, vivacity, libido, and all-around energy, it’s a good moment in our lives, it is the “prime,” as it’s been described.8 Yet, as additional statistics show,9 many young adults despise their youth, they have a “fear of adulting” that makes them regard their stage in life as a miserable burden rather than a joyous occasion. This conflicts with the high praises that many wise men of the Classical and Middle Ages sung of youth, the vicissitudes experiencing in becoming a man or woman, in sparking and courting love, and the other blessings of this life-stage.

As of late, owing to the reading I’ve been doing during this hiatus, I’ve taken a liking to the Latin aphorism “Ignoti nulla est curatio morbi,” which translates to, “There is no cure for an unknown disease.” What this has taught me is that any effort to treat something must be preceded by understanding. There’s a reason why back when COVID was just starting the headlines often spoke of the rush by medical scientists to sequence the genome of the virus so as to more easily and rapidly develop a cure. So, as it concerns the variegated issues that face and demoralize our youth outlined above, which we can classify as a disease (like much of modernity), we need to better understand what it means to be young to heal the pains of the young. I see now this might be a sentiment that slightly diverges from the implications of that Latin aphorism, but I hope you can still keep track with what I’m doing here.

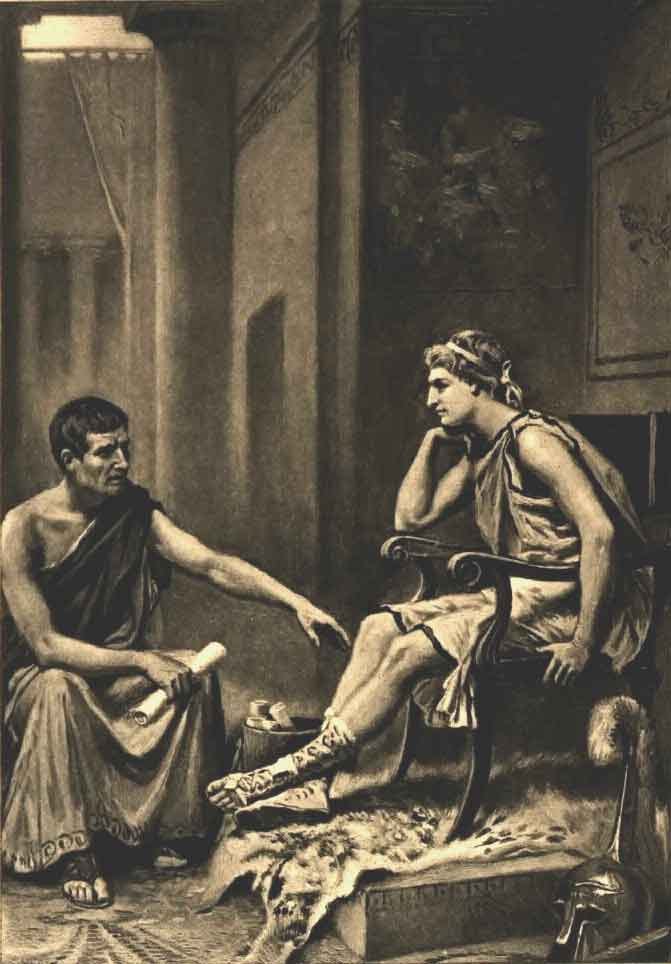

So, suffice to say, what I wish to do is define and demarcate just what it means to be young, even, for greater clarity, what it means to be in all the different stages of life. In doing so I will be taking inspiration from a well-liked and much-noted influence of mine, Aristotle. He alone makes me contemplate the validity of the “virtuous pagan,” and it is to him I defer to for many interests, for he was a man of many interests.

In his lesser-known Parva Naturalia, a collection of essays discussing subjects related to the nature and operation of the body and soul, which is one installment in the corpus of Aristotelian biology, Aristotle engages in a relevant discussion in the constituent essay “On Youth, Old Age, Life and Death, and Respiration.” In this essay he goes over a concept important in classical medicine known as the calidum innatum, or “vital/innate heat.” The vital heat is produced by the heart and moved through the body by the circulatory system, a belief derived from the fact that blood is warm, and ancient medical argumentation that established warmth as essential to life. This can be seen in Aristotle’s discussion of respiration and heat towards the end of this essay:

Everything living has soul, and it, as we have said, cannot exist without the presence of heat in the constitution. In plants the natural heat is sufficiently well kept alive by the aid which their nutriment and the surrounding air supply. For the food has a cooling effect [as it enters, just as it has in man] when first it is taken in, whereas abstinence from food produces heat and thirst. The air, if it be motionless, becomes hot, but by the entry of food a motion is set up which lasts until digestion is completed and so cools it. If the surrounding air is excessively cold owing to the time of year, there being severe frost, plants shrivel, or if, in the extreme heats of summer the moisture drawn from the ground cannot produce its cooling effect, the heat comes to an end by exhaustion. Trees suffering at such seasons are said to be blighted or star-stricken. Hence the practice of laying beneath the roots stones of certain species or water in pots, for the purpose of cooling the roots of the plants.

The logic, and even the crude empirical observations, the ancient Greeks used to formulate this system is truly interesting. It makes sense, it follows from the presuppositions and observations they had of the human body and its operations, even if, as we now know, they were pretty much incorrect.

Now, since they were incorrect, how do I intend to apply such an understanding believably and relevantly to modern human life? Well, there is two ways: one, whether we must allegorize or “shift-upward” (i.e., move the language of the “vital heat” into the realm of the spiritual) Aristotelian biology,10 it’s relevance can still be perceived, even in everyday lingo, where we can find idioms and proverbs related to heat and its role in life; second, as I’ve read Ed Feser’s Aristotle’s Revenge, I’ve come to learn there are important philosophical, methodical, and conceptual elements in Aristotle’s wisdom that still ring true today, being of service to modern philosophical and scientific undertakings, or even just serving as good rhetoric.

That’s pretty much what I see the calidum innatum as, all that I can see it as, “good rhetoric.” But that’s no cause for concern. Just like good architecture is, structurally, the proper arrangement of physical parts, and, functionally, a means to lift up man’s thoughts to greater things (consider the designs of ancient cathedrals and castles), so too is rhetoric the proper arrangement of words with the function of lifting up man’s thoughts by what he reads or hears. Given my view of the constitution of the human being, I consider this to be activities of the spiritual realm, which is anterior to the physical,11 and thus affects it insofar as it too is affected (such as by spiritual malaise or joy). So, given this, I will still be making use of Aristotle’s wisdom, and explaining how it can be reworked to inform us about what youth, and life at-large, is about.

Human life begins in infancy, the main life-stage. At this point, the vital heat is not really there, with the infant’s capacities essentially all in the hands of his parents. Infancy is an entirely parental life-stage, derivative we might say, and constitutes the sparking of the flame within. However, once the spark does catch it begins burning marvelously, and you can think of all the milestones a child can begin racking up once they pass the one-year mark.

This is followed by childhood, which can also be called or later called “pubescence,” which sees the flame burning in full force, heat coursing through the body. It is still growing, but it’s not incipient like in infancy. However, we must pause to consider an important fact about fire: it burns. While fire can do many creative things, it also has the capacity for destruction, for harm. Accordingly, we must realize that the vital heat can harm. How do we prevent the vital heat from catching and creating an inferno? This is what we must ask ourselves at the stage in life when a human’s vital heat is surging and growing, and thus what also defines this stage of life: setting stones around the flame. Like in real life, stones put around a fire serve the function of preventing flames from surging outward or spreading too far, causing an out-of-control fire. Similarly, the stones we place around the vital heat of children seek to prevent them from getting burned, by themselves or others. They are the lessons and rules we teach kids to take to heart, even if it might take later in life for them to truly understand it.

Notice I collocate “lessons” with “rules,” for I don’t want to give the impression that these “stones” can only constitute “Thou shalt nots,” that rather than being rigidly dogmatic these can also be experiential stones. Case in point, a lesson I’ve learned is how children are actually disadvantaged by being overprotected and regulated, that in life getting a boo-boo (or, as we grossly conflate it as, “trauma”) as well as actually being given the opportunity to act for some time without parental oversight, actually serves a maturative and didactic function for developing kids.12 Otherwise, you get that weird kid who is “sheltered,” invariably weak, or, perhaps worse, you have an environment tyrannized over by an Oedipal mother. So, we’re reigning in the roaring flame of pubescence, but we’re not smothering it, making it die out just as it begins. This is how we can see the malaise of maladjustment many kids raised under the auspices of modernity suffer from.

Then we get to the life-stage of youth, or adolescence, defined earlier as somewhere around age 16 into the 20s. What is youth? Youth is controlling the flame, which is distinct from reigning it in, in a subtle way: while stones placed around the fire might keep it from catching, it can still pose a danger. Anyone who’s been near a bonfire can attest to this fact: it can be as secure as possible, but if you get too close you’ll get singed! Similarly, even if the fire can’t grow outward, it can grow upward, and tall flames begin to smoke. Too much smoke, and you can begin to choke and not see as well. It will leave you dazed. So, youth can perhaps be even better seen as “curating” the fire; to shift for a moment the analogy in use, think of the bonsai tree, which is carefully shaped and pruned into a desired form by its owner. Youth is a time for self-discovery, it’s defined by vigor and vivacity, it’s when someone establishes who they are, what they are, and even more so whose they are (through matrimony). In doing this we take the powerful roar of the flame within and seek to use it for our ends, again, controlling it, curating it.

It is here we can see one of the most basic ways in which modern society disadvantages the young. As it is usually approached, once someone turns 18 then they become an adult, then they are to take on responsibilities and burdens and figure out who they are. The age 18, a purely statutory phenomenon, has blinded us to the true realities and nuances of adolescence and life. Just because legislatively “adulthood” begins at age 18 doesn’t mean culturally, mentally, or praxeologically does adulthood begin then, but because so much of our society, hyperpolitical and hyperlegislated as it is, has handed over our faculties of identity-forming and community to legislative diktat we have lost track of this.13 The long and short of it is that the mentality that’s come to affect most parents and countrymen of the 18-year-old (the “legal adult”) is that “Now your job begins.” This is fundamentally at odds with centuries of cultural expectations and norms, human nature, and has produced numerous manchildren who are “legally” adults yet haven’t the faculties to behave like one (like the widespread “fear of adulting”), but because statutorily they’re of majority their parents cast them to the wind (or colleges) and act as if their maladjustment is a total mystery.

Rather, here’s how centuries of civilized people treated adolescence: a time of progress, wherein children grow into their adult privileges and duties, rather than statically receive them a minute after 11:59 PM on the eve of their eighteenth trip around the Sun. The dynamic nature of adolescence can be seen in the word we often apply to its end result: maturity. This derives from the Latin adjective maturus, which means “ripe” (if not just “mature”). Accordingly, in Latin literature maturus is usually applied to the cultivation of some fruit or other cultivar, and as anyone with any sort of agricultural experience (even just a farm tour) can understand: ripeness is not static. Numerous conditions condition when an apple becomes ripe, ready to be plucked and achieve its completion (in being used as satiation for a human). Think of many of the accomplishments of classical Western civilization, and who accomplished them, and more so when: Alexander the Great was 23 when he decisively won the Battle of Issus (in fact, Alexander has been given royal authority as young as 16); Michelangelo was 24 when he sculpted the Madonna della Pietà; Joan of Arc was 17 when she lifted the siege of Orleans (and only 19 when she met her end); Mozart was a court musician for the Prince-Archbishopric of Salzburg by age 17, and accomplished all that he did before the age of 35; and the list could keep on going.

The point I’m making here is that adolescence is not the time of revelry and to burn oneself out of all childishness so that on 18 things change on a dime, nor that things change on the dime, but that once childhood is shed (around the mid-to-late teens) now one’s maturation (ripening) begins. Imagine if the way we raise kids and make them think about themselves today had been applied to any of the aforementioned historical figures. The ensuing vacuum of merit and accomplishment would be harrowing. There’s a reason, as Charles Murray has pointed out, that classical Western civilization was defined by numerous feats of human creativity, but the modern West is rife with (civilizational) depression and encroaching economic destitution.14

In my own life I experienced the tension between these two cultures, the culture of “coddling” and the culture of “adolescent potential” (as we may call it). My mother did her best to raise me under the latter style, and progressively, as it seemed to me, “pulled the rug out” from under myself. I, at the time, found this a terrible thing for her to do and internalized much resentment. However, in hindsight, I came to realize just how truly infantile and maladjusted I was (as plenty of people could line up to confirm), and that her efforts were in the right and compelled me to adjust and grow and mature. It took longer than it should’ve, many factors impeded this, but it happened, I’m thankful to say. However, my situation was unique, in which I actually had a mother with a strong presence and a strong sense of what it meant to be a parent, as well as those “many factors.” For most people? Their parents themselves were coddled, so they have absolutely no sense of what it means to be a parent, in addition they’re surrounded by a culture of coddled pseudo-adolescents, and a Big Brother who keeps the gravy train running from cradle to grave. Scale this up while taking the behavioral and psychological consequences into account and you find yourself taking off the proverbial blindfold to find yourself on the proverbial train barreling towards the proverbial cliff.

This is, essentially, what went wrong with youth, in case you’ve been waiting for the answer to this whole article. Feel free to keep reading past if you’re still interested.

The next stage of life is the peak of life, when life “comes into its own.” This is “adulthood,” or “maturity,” traditionally indicated by the consecration and consummation of marriage. What defines adulthood? Well, to continue with the vital heat analogy, that would be self-mastery. In particular, as an adult we have now reigned in and curated our flame, it has become a valued and meaningful part of our persons. Accordingly, in contrast to having an adversarial or fearful relationship to the flame within as we had throughout the earlier times of our lives, we now have an instrumental relationship. You see, while in infancy, childhood, and adolescence/youth we saw the flame as something that could fizzle, burn, singe, or choke, now we see it as something that could smelt, illuminate, or feed. We use it for the good of ourselves, our families, and our communities.

However, as Aristotle warns us, eventually the cold of life that cools the flame periodically to bring slumber will grow stronger as the flame grows weaker, and brings upon the eternal slumber. This is senescence, the last stage of life. With the flame starting to go out, as we begin to go out of the world as we came into it (weak, dependent; Ecc. 5:15-17), what do we do? An appropriate understanding of elderliness can help us face it with greater ease. Simply put, with our governing metaphor of the vital heat, as already indicated, senescence is the heat growing weaker, and is the inverse of our infancy. So, just how infancy is concerned with sparking the flame, senescence is fanning the flame. As one ages, they quite literally begin to lose their spark, and so the challenge is how to hold onto that spark for as long as one can. This is why old age/the retirement years are perceived as the time to do all those things one couldn’t do when young (as they were committed to controlling their flame), the “golden years.” This is when we take our trips to the Florida Keys, this is when we take a few thousand dollars out of the checking account to purchase that old hot rod, or engage in some other indulgence.

This is all well and good, but it must be done with modesty. And what would that constitute? Well, just as infancy’s sparking of the flame is usually done mediatorially (parentally; by others to us), senescence’s fanning of the flame is done beneficently, grandparentally, by us to others (our descendants). The entertainment of retirement is not done for the sake of oneself, but the sake of others, to relish in all the accomplishments of our youth, reaping what we had sowed and sharing the bounty of our harvest. Thus, grandparents often involve their grandchildren in their plans: the trip to the Florida Keys is never done alone, but the whole family is invited; the hot rod is never just to take to the grocery store, but to take the grandkids on a joyride; the money used to upgrade the living room with a nice TV and surround sound isn’t just for our sake, but for family movie nights. After all, we’re going to be dead in a few years, why are we amassing all this luxury now if not for others?

Then comes death, and we stand before God to account for our life, and are told, “Well done, good and faithful servant.” In order to get here, however, we must make sure we have cultivated a life of virtue, which comes through maturity, maturity which, if offset by calamity or neglect, will be sorely missed later in one’s life as they struggle with all the vicissitudes it has to offer. Getting started or getting back on track shouldn’t scare us, for the Good Lord has done His best by us and ordained the local church, the household of God, to provide us with the shepherding and the parenting we might have lacked all our lives. As it has been, apocryphally said, “The church is not a museum of saints, but a hospital for sinners.” Through the healing ministry of the Church, though this might be something in need of renewal, we can all have a Damascene moment wherein the scales from our eyes, or, alternatively, the flame roars forth from within, ready to take on life in good stride.

Often, also, able-bodied, heterosexual, and White.

See Michael Rectenwald, Springtime for Snowflakes; idem, Beyond Woke.

For an overview of what ills are facing/have been put upon men see Warren Farrell and John Gray, The Boy Crisis.

Against this misandristic and gender-deconstructionist narrative see Warren Farrell, The Myth of Male Power, and comments throughout Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules For Life.

On the consequences and lies of modernity’s egalitarianism and feminism see Alice von Hildebrand, The Privilege of Being a Woman; Sarah Hill, This is Your Brain on Birth Control; F. Carolyn Graglia, Domestic Tranquility; Elisabeth Elliot, Let Me Be a Woman.

A representative sampling: Molly Shen, “Young adults drag US down to 23rd in world happiness rankings, report shows”; Matt Richtel, “‘It’s Life or Death’: The Mental Health Crisis Among U.S. Teens”; Jim Sliwa, “Mental Health Issues Increased Significantly in Young Adults Over Last Decade”; “Mental Health Challenges of Young Adults Illuminated in New Report.”

As is endorsed by the UN, which I suppose is a credible authority, at least for these more minor matters.

An appropriate term, considering the Latin root means “first,” so the “prime of life” is the “first of life,” indicating that only now is such a person truly experiencing their life, now being independent and able to surpass the dependency and limitation of childhood.]

This is pretty much the route I’ve taken, as it has the most efficacy at salvaging the utility of Aristotle’s wisdom while acknowledging its usurpation by the findings of modern medical science.

Anterior, a very important word choice, distinct from superior, so as to maintain some distinction but without falling into neo-Gnostic misery.

See Jordan Peterson’s interview “Bad Therapy, Weak Parenting, Broken Children | Abigail Shrier | EP 427,” esp. from the 40-minute mark on.

Not to belabor this point too long in an otherwise unrelated article. Suffice to say, what I’m tapping into here is the notion that “legislation” is fundamentally different from “law,” the prior being a creation, the latter being a discovery arising organically out of a community’s dynamics and natural law. By becoming saturated in legislation reality essentially becomes a top-down political enforcement, rather than a bottom-up holistic worldview, which has many consequences. On this distinction and issue see N. Stephan Kinsella, “Legislation and the Discovery of Law in a Free Society,” Journal of Libertarian Studies 11:2 (Summer 1995): 132-181; Ugo Stornaiolo S., “A Tale of Two Legal Systems: Common Law and Statutory Law”; David Dürr, “The Inescapability of Law,” Journal of Libertarian Studies 23 (December 2019): 161–70; Jeffrey Tucker, “Repeal the Drinking Age”; Bruno Leoni, Freedom and the Law.

See Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment, esp. 383-458; cf. also Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, The Coddling of the American Mind; Pat Buchanan, The Death of the West.